The pencil test is a method of assessing whether a person has Afro-textured hair. In the pencil test, a pencil is pushed through the person's hair. How easily it comes out determines whether the person has "passed" or "failed" the test.

This test was used to determine racial identity in South Africa during the apartheid era, distinguishing whites from coloureds and blacks. The test was partially responsible for splitting existing communities and families along perceived racial lines. Its formal authority ended with the end of apartheid in 1994. It remains an important part of South African cultural heritage and a symbol of racism.

Background

The Population Registration Act required the classification of South Africans into racial groups based on physical and socio-economic characteristics. Since a person's racial heritage was not always clear, a variety of tests were devised to help authorities classify people. One such test was the pencil test.

The pencil test involved sliding a pencil or pen in the hair of a person whose racial group was uncertain. If the pencil fell to the floor, the person "passed" and was considered "white". If it stuck, the person's hair was considered too kinky to be white and the person was classified as "coloured" (of mixed racial heritage). The classification as coloured allowed a person more rights than one considered "black," but fewer rights than a person considered white.

An alternate version of the pencil test was available for blacks who wished to be reclassified as coloured. In this version, the applicant was asked to put a pencil in their hair and shake their head. If the pencil fell out as a results of the shaking, the person could be reclassified. If it stayed in place, they remained classified as black.

Effects

As a result of the pencil test, combined with the vagueness of the Population Registration Act, communities were split apart on interpreted racial lines. In some cases, members of the same family were classified into different groups, and thus were forced to live apart.

In one famous case, a somewhat dark skinned girl named Sandra Laing was born to two white parents. At age 11, she was subjected to a pencil test by "a stranger" and subsequently excluded from her all-white school when she failed the test. She was reclassified from her birth race of white to coloured. Sandra and the rest of her family were shunned by white society. Her father passed a blood-type paternity test, but the authorities refused to restore her white classification.

Reputation and legacy

Although the pencil test ended with the end of apartheid in 1994, the test remains an important part of cultural heritage in South Africa and a symbol of racism worldwide. For example, a Southern Africa newspaper described incidents of mobs "testing" the nationality of suspected (black) foreigners as a "21-st century pencil test". Another South African commentator describing the same incidents called them "a gruesome re-creation of the infamous pencil test of the apartheid regime".

In 2003, a The New York Times writer called the pencil test "perhaps the most absurd" of the many "humiliating methods [used] to determine race". Frommer's calls the pencil test "one of the most infamous classification tests" of apartheid. Others have referred to it as "degrading" and "humiliating" and an "absurdity".

In the 2009 film 'Skin",

A man sticks a pencil into the young Sandra's short hair, a re-creation of the “pencil test” used by some government boards to judge race. The film was based on Sandra Laing. A woman who was born to white parents but reclassified as Coloured during the apartheid era in South Africa as she has dark skin.Sandra is the feature of the documentaries In Search of Sandra Laing (1977), Sandra Laing: A Spiritual Journey (2000) and Skin Deep: The Story of Sandra Laing (2009).

Sandra was born in Piet Retief, a small conservative town in apartheid South Africa. Both Sandra's parents and all her grandparents were white. Her older brother was also white but Sandra and her younger brother had African features. Sandra's parents were both members of the National Party and supporters of the Apartheid system.

During apartheid, schools were segregated; however, since both her parents were white, she was sent to an all-white school. Her parents hoped that as she got older she would get lighter; however, instead she grew darker and her hair became more tightly coiled. At boarding school she was shunned by the other students because of her skin color.

Legal battles

When Sandra was 10 years old, the school authorities expelled her from her all-white school based on the complexion of her skin and a failed pencil test. She was escorted home by two police officers who refused to tell her what she had done wrong. Her parents fought several legal battles to have her declared white. Her father underwent a blood typing test for paternity in the 1960s, as DNA tests were not yet available. The results were compatible with him being her biological father.

Later years

Since she was shunned by the white community, Laing's only friends were the children of black employees. At age 15, she eloped with a black South African to Swaziland. She was jailed for three months for illegal border-crossing. Her father threatened to kill her and broke off contact with her. They never met again and she remained estranged from her family, with the exception of secret trips to visit her mother at times when her father was away from the home. When her parents moved away from Piet Retief, the clandestine visits were no longer possible and Laing lost contact with her family completely.

Years after the death of her father, Laing managed to track down her mother, Sannie, in a nursing home shortly before the woman died in 2001, but a succession of strokes had stolen Sannie's memory. A book called When She Was White by Judith Stone reports that Sannie did remember Sandra and was happy to see her. As of 2009, Sandra Laing's brothers, both of whom were still alive, were maintaining their refusal to have any contact with her, though she said in an interview that she continued to hope they would some day have a change of heart.

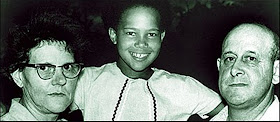

Sandra Laing with her parents.

Sandra with her children

Young Sandra Laing

No comments:

Post a Comment